Fort Hancock, also portrayed in our previous blog posts, is a community of hard-working individuals. Even though this is a desert, it is also a flood-prone area. But people love their town. They like its quiet environment and enjoy harmonious relations with their neighbors. Many people in this community are highly motivated to serve one another and to serve Texas.

The Hudspeth County Judge, Joanna MacKenzie, is one of them. She grew up in this community and is passionate about helping Fort Hancock overcome historical inequities. From her position as a government decision-maker, she helps people who are affected yearly by “arroyos,” the powerful streams of water that inundate property and put people at risk. Judge MacKenzie met a long-term resident who said when it rains, she just opens her back and front doors and lets the arroyo run through. Then she cleans up the mess the best she can because she knows it will come again soon. What is unthinkable for some has become normalized in her life.

Judge “Jojo,” as she prefers to be called, approached the DRIP team to understand why she could not find a way to qualify for federal and state funding that could help her plan and provide solutions. Our team spent the past year looking for flood-related risk data to provide evidence for what is happening in her community. However, Fort Hancock is a data desert; although the community floods every year, there is no accurate, regulatory data to demonstrate what happens to the state and federal agencies who could provide assistance. Quite often funding and policy decisions are made by people who assess needs based on numbers, measurements, and tangible evidence.

As Sergio Quijas, County Commissioner of Precinct Two, drove around town describing flood damage for the DRIP team, he explained that the only flood map available does not reflect the reality of their situation. The last time it was updated was 1985 when he had not even been born. And during his life, he has seen repetitive flooding in the house where he grew up and where his neighbors and family live.

The challenge for the DRIP team was to effectively convey the community’s situation and to treat their local knowledge with the utmost respect. After meeting Judge Jojo, Sergio, and several trusted and committed religious leaders in Fort Hancock, the research team and the community co-created a plan of action. The research team would create a new map and then give it back to the community. Together, the DRIP team and the community leaders agreed to include images and stories about flooding on the map. During June and July of 2023, trained Fort Hancock community members went door-to-door to collect flooding-related photos, videos, and stories for the map that will be available for the community to share. Besides providing a good foundation for evidence-based decisions, this map will be a rich and multilayered tool to help people living in and working with Fort Hancock to make sense of their present and future complex relationship with water.

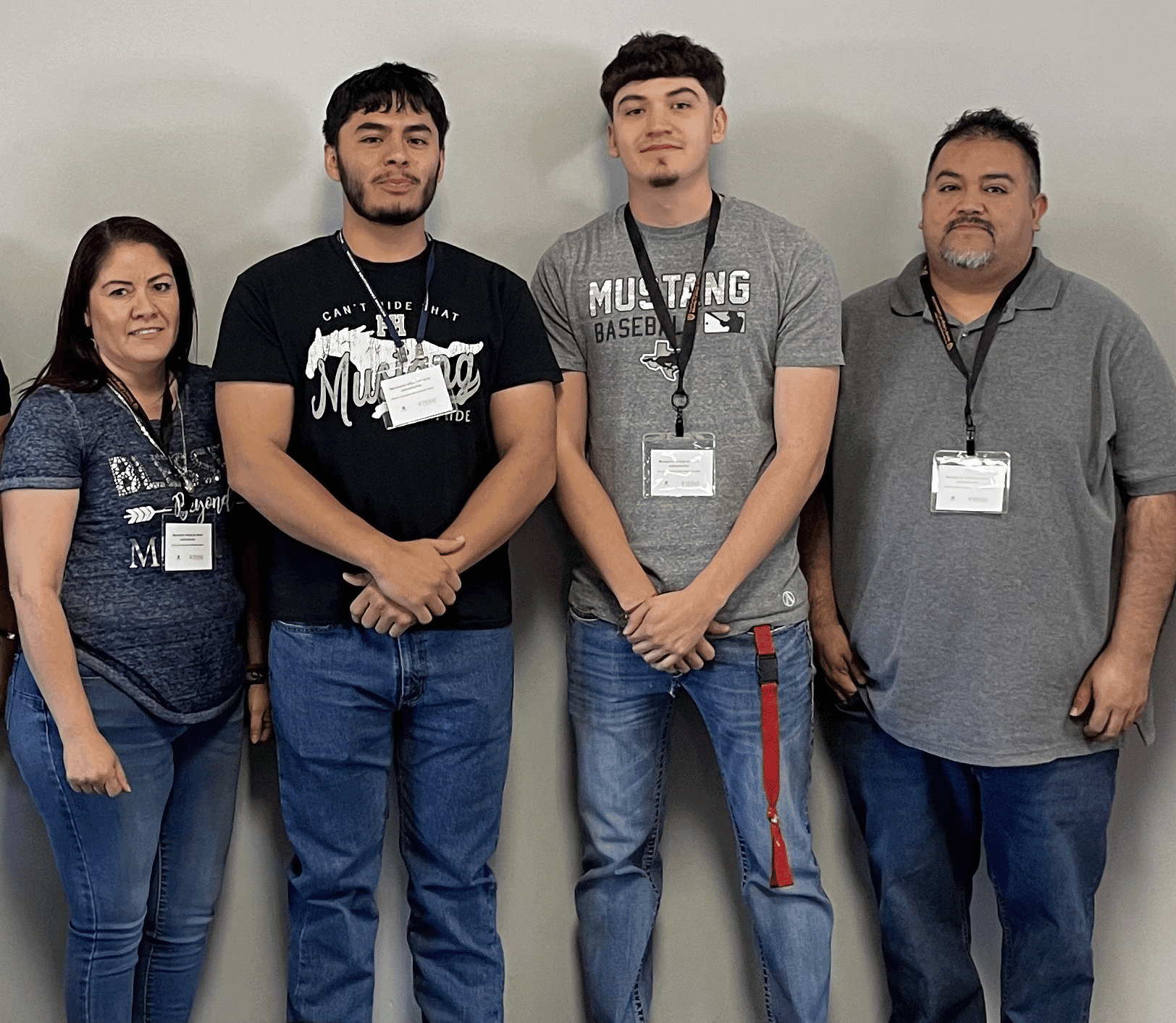

Data collection was a process grounded in the very heart of the community because it was led by its members. Four residents visited each of their neighbor’s homes, one by one, to learn about their experiences with arroyos. The data collection team was comprised of two men in their twenties, one single father, and a woman who was very connected to the Fort Hancock community. Bryan and Josh, the young men, dreamed of being able to have a family in this community and watch their children grow up safely. Willy, the family man, was personally affected by the arroyos when they ran through Fifth Street destroying all they could as they raced toward the Rio Grande River. He and Juve, the most experienced part of the team, visited the most affected part of Fort Hancock and spread the word about creating the map. Juve explained that the data desert made her community look like they had no flooding problems, and they all had to work together to change that perspective. The data collection team did a great job as they were motivated by what became one of their mottos: “We are helping our community get on the map!”

The community was an active partner in constructing knowledge and we worked from a perspective of sharing ownership between researchers and the community. The experience was also full of “aha” moments. Because one of the main communication channels in Fort Hancock is in-person communication at meetings, the team used them to explain the project. Overall, meetings were mutual learning moments where the team was privileged to witness sparks of the spirit that drives public participation. Some of those moments occurred when people looked at hydrological maps prepared for them to see their panorama. When comparing other towns’ flood maps with their own, there were expressions such as: “How is this fair? The map shows they [Dell City, another city in Hudspeth County, Texas] flood, but it doesn’t show our flooding in Fort Hancock. We must do something to fix this!” Other people spoke of action, and that they want the problem to be fixed at the very core: “We will gather people and walk with those who make decisions […] If physical work is needed, we will do it; what we want is for our town to be inhabitable.” Naturally, because the project revolves around disasters, there were also hard moments. Some phrases used at the meetings were somber: “When it rains, we are trapped. I have a son with a disability. What happens if I need to go to the hospital with him? I can’t.” “My son with Down syndrome hears rain or thunder and gets anxious and terrified.”

Gathering data from a data desert is one of many steps necessary to begin to address severe flood-damage, but this encounter between a highly-technical academic team and the community of people who are the heart and life of Fort Hancock yielded a valuable lesson. The co-creation of data, power sharing, and listening to community members themselves provides deep meaning rarely acquired through other types of data generation processes. The academic team doing the fieldwork feels enriched and honored because we were allowed to work with this community. As Commissioner Sergio Quijas said: “This project has made us feel like we belong. Other people come into our community once and promise to help us, but we never see them again. The DRIP team has come back repeatedly, understood what we want to do, and allowed our community to build capacity.”